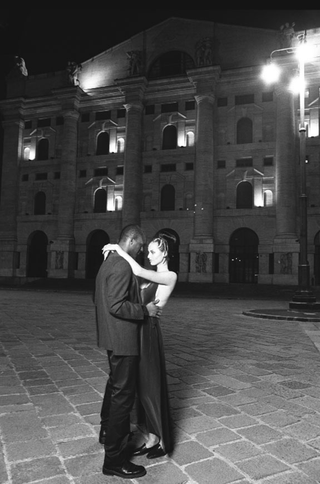

“There are many nights of Milan in my memory. Many different kinds of nights, I mean. But the first night that comes to mind now, I am sure, is unique. The war had just ended, those last two terrible years finally behind us.

And so the blackout ended as well—the long nights when the whole city remained in darkness to hide from enemy bombers.

Naturally, the blackout ended all at once, from one night to the next. And there I was, out in the street, when, in the first shadows, suddenly all the streetlights flared on, and in the houses people threw open their windows onto brightly lit rooms. Were they shouting?

Waving their arms? I must have walked for hours before deciding to return home.

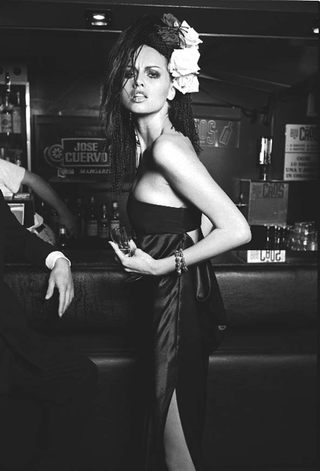

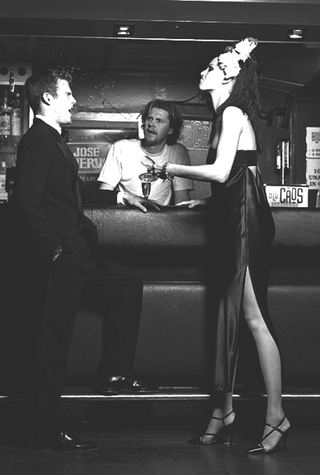

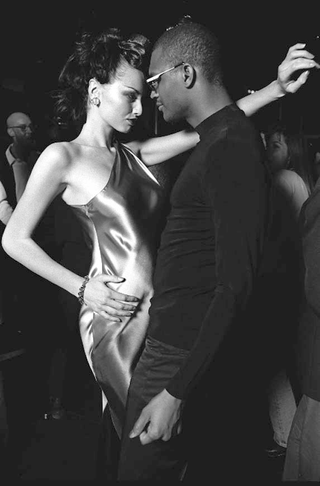

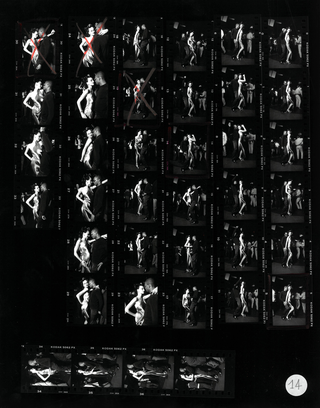

Then there were the nights of postwar Milan. We were always at the theater. And afterwards we would wander the streets, speaking of the world, of the universe, with not the slightest doubt about our own competence. Every so often we began to play—after all, we were little more than boys. And when someone would open a window and shout down that it was late, that it was time to sleep, we felt a shiver of scornful pride. Vanity, foolishness, of course. But it seemed to us that it was enough to fill the whole night, one night after another.

It would end with us walking through the streets again, for hours, with the last friend still by my side. I would walk him toward his home, and he would walk me toward mine, back and forth. Fausto Salvadori—when I saw he was really determined to leave me, I would start making him talk about girls. Then he would follow me like a little dog, accompanying me to the corner of my street, no matter the hour.

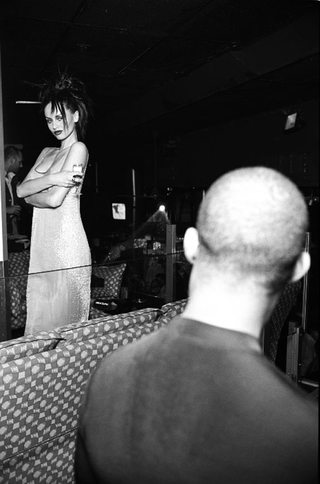

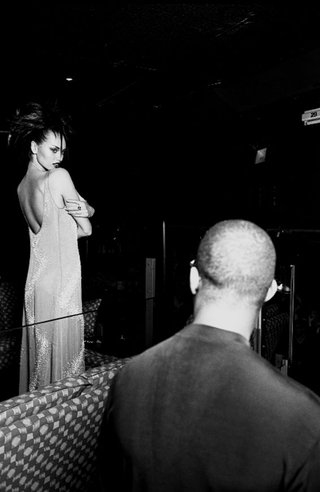

And then, in my memory, suddenly, there plunge the bleak nights of the Seventies. Dark—even though all the streetlights were lit. Like a scene from an expressionist film—one expected the houses to tilt, to slant askew. Very few people on the streets. When footsteps sounded behind you, you didn’t even turn to look; you simply crossed to the other side. People went out little at night, and if they did, they tried to stay out as briefly as possible.

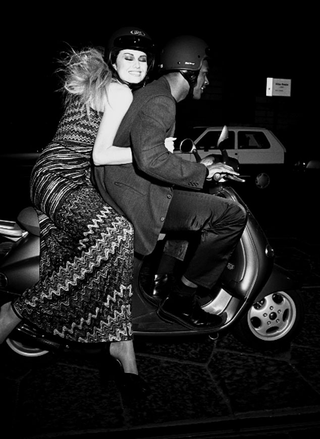

When, at night, I began once again to cross half the city on foot—from the center toward the east, my Milan—I always loved reaching Porta Venezia and stepping onto Corso Buenos Aires. At any hour, there are bright lights and cars passing by. Parked cars, newsstands still open with people buying papers. Porta Venezia is truly a frontier, even at night. A frontier dividing two very different worlds. Toward the center lies the Milan of the well-to-do neighborhoods. Beyond Porta Venezia (once called Porta Orientale) begins a “lower,” more working-class Milan—yet much more alive.

There live Arabs, Africans, with their restaurants, their cafés…

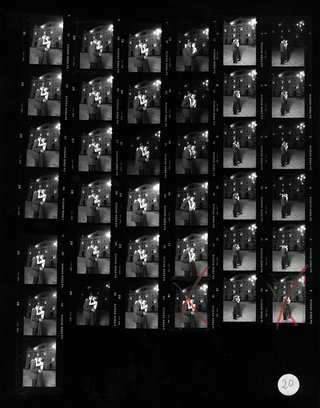

According to one study, two hundred thousand people come every evening to spend the first part of their night in Milan. From time to time, late at night, along Loreto or Viale Monza, a car crammed with young men races past, stereo blasting at full volume. Even in winter, with windows shut, one hears, violently insistent, the pounding of electronic drums. Boom boom boom boom…

And then, when it is very late indeed, if one had the kind of keen ears found only in fairy tales, one might even hear the faint hiss of spray cans in the hands of graffiti artists. People determined to leave their mark on the city walls at any cost—much as the travelers from the North did in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, carving their names into monuments here in Italy. Except that they used a metal point to engrave.

Even in Milan, if nothing else, the night brings with it that trace of madness that, after all, is necessary. A kind of excited serenity, a taut distraction, something like a small, gratifying waste of energy…”

(Emilio Tadini, Sera a Milano - Quel quasi niente di follia, in “Città Milano”, n. 1, Ocotber 1997)

Social

Contatti

archivio@carloorsi.com