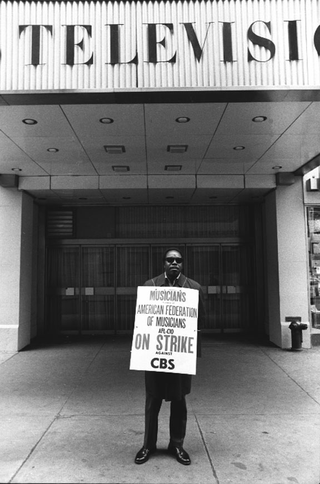

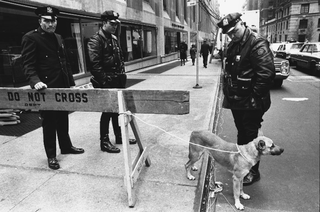

In the 1960s, New York definitively established itself as a hub of contemporary art, surpassing Paris and asserting its dominance on the international scene thanks to the explosive energy of Pop Art, Minimalism, and early conceptual and process-based experimentation. It is a decade of profound social transformation, marked by civil rights movements, protests against the Vietnam War, and a growing politicization of culture.

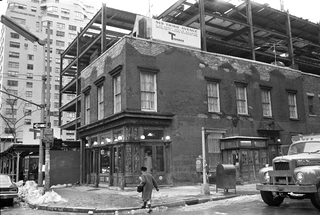

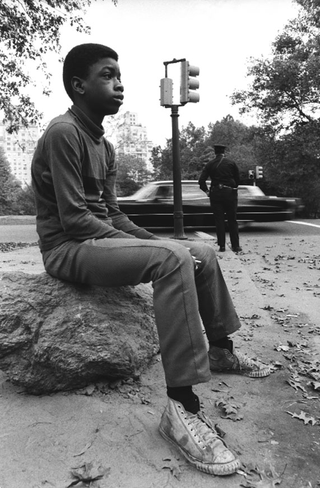

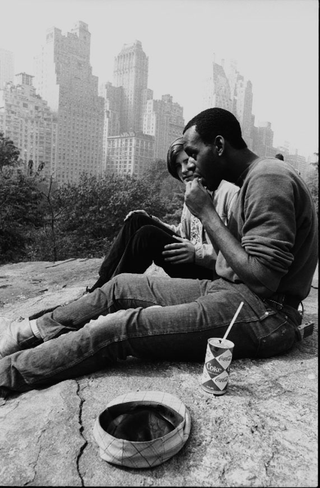

As the civil rights movement shook the foundations of America, a new energy, suspended between protest and creativity, filled the streets of Manhattan. Harlem continued to be an epicenter of black culture and resistance, Greenwich Village pulsed to the rhythm of counterculture and folk music, while new artistic experimentation saw the light of day in the nascent galleries in SoHo. In a year marked by political assassinations and radical transformations, New York was both mirror and engine of change.

The year 1968 marked a turning point, not only for American society as a whole, but also for the New York art world. In this context, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), an institution central to the legitimization of the historical and modern avant-garde movements, found itself at the center of a heated debate. Increasingly, artists and critics (including Hans Haacke and the Art Workers' Coalition - AWC) are beginning to question the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion operated by large museums, which are accused of upholding an elitist and complacent vision of art, distant from the political and social urgencies of the present.

Despite these tensions, or perhaps in response to them, MoMA continues to organize exhibitions that will have a lasting impact on art history. Among the most significant are: The Art of the Real: USA 1948-1968 dedicated to American art from Abstract Expressionism to Minimal art; a tribute to Martin Luther King, held six months after his death, composed of works that would later be sold to benefit the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, curated by Pontus Hultén, which explored the ways in which artists, through their works, reflect on the theme of technology.

In the 1960s, New York definitively established itself as a hub of contemporary art, surpassing Paris and asserting its dominance on the international scene thanks to the explosive energy of Pop Art, Minimalism, and early conceptual and process-based experimentation. It is a decade of profound social transformation, marked by civil rights movements, protests against the Vietnam War, and a growing politicization of culture.

As the civil rights movement shook the foundations of America, a new energy, suspended between protest and creativity, filled the streets of Manhattan. Harlem continued to be an epicenter of black culture and resistance, Greenwich Village pulsed to the rhythm of counterculture and folk music, while new artistic experimentation saw the light of day in the nascent galleries in SoHo. In a year marked by political assassinations and radical transformations, New York was both mirror and engine of change.

The year 1968 marked a turning point, not only for American society as a whole, but also for the New York art world. In this context, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), an institution central to the legitimization of the historical and modern avant-garde movements, found itself at the center of a heated debate. Increasingly, artists and critics (including Hans Haacke and the Art Workers' Coalition - AWC) are beginning to question the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion operated by large museums, which are accused of upholding an elitist and complacent vision of art, distant from the political and social urgencies of the present.

Despite these tensions, or perhaps in response to them, MoMA continues to organize exhibitions that will have a lasting impact on art history. Among the most significant are: The Art of the Real: USA 1948-1968 dedicated to American art from Abstract Expressionism to Minimal art; a tribute to Martin Luther King, held six months after his death, composed of works that would later be sold to benefit the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, curated by Pontus Hultén, which explored the ways in which artists, through their works, reflect on the theme of technology.

Social

Contatti

archivio@carloorsi.com